Is your contemporary painting more temporary than you think? Is the title to an early 1960s art-conservation guide that has always amused the author. It was a serious little publication by Louis Pomerantz the founder of the Art Institute of Chicago’s conservation laboratory and an attempt to help artists of the day use materials to paint pictures that collectors would be confident survived over time.

The inference was that artists from the Second World War onwards are interested only in artistic expressions to the detriment and lack of permanence of the work of art itself. The underlying belief is still current that the Old Masters, in practice, anyone working before 1850 were, one and all, superb technicians smugly virtuous artists who used only the finest materials that they prepared with carthusian patience. However, it was a commonly held view even as long ago as Pliny the Elder, born in Como in 23 A.D. in his Natural History that artists, if you do not watch them, will steal you blind and, given the opportunity, will try to substitute the expensive lapis-lazuli, Chinese vermilion and pure gold you have supplied them with for the creation of your painting with low-grade substitutes.

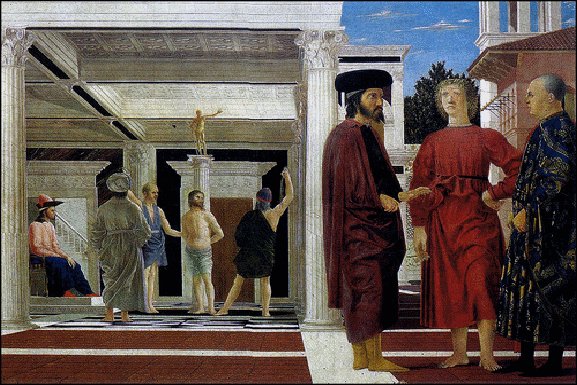

Piero della Francesca, Flagellation of Christ c.1455–1460

Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino, Italy.

This prudent attitude towards artists continued into the Renaissance. The innovative early fifteenth century painter Piero della Francesca despite been recognised as a leading artist of his day was often contractually obliged to use specific colour in his works such as genuine and costly ultramarine for the blue for the Madonna’s robes or the sky tints, paid only a nominal deposit as a guarantee and frequently sued in court for failing to deliver the painting contracted for or not delivering it on time. When the author was a member of the Istituto Centrale del Restauro in Rome during the restoration of Piero della Francesca’s Flagellation of Christ he noted that part of the painting’s problems arose because the artist used substandard chalk priming to prepare the timber panels on which he painted.

Ill-conceived techniques, unproven and experimental materials are the explanation for Leonardo da Vinci’s technical fiasco of a fresco, the Last Supper (Il Cenacolo) in Milan and his self-destructing lost Battle of Anghiari fresco in Palazzo Vecchio, Florence. Practical experience by anyone who has owned an old painting can teach that the canvas or timber support, the paint layer, stretcher (the four pieces of timber on which the canvas is stretched) and the varnish can be extremely fragile Some Riviera collectors have paintings by the 18th. Century English Old Master Sir Joshua Reynolds and know this to their chagrin.

Technically, he is a rogue painter in the manner of Leonardo da Vinci. Like Leonardo he had the same natural curiosity and love of experimentation and produced equally disastrous results. Reynolds fell in love with a recently introduced dark brown colour, bitumen, that produced deep rich blacks and subtle glazes. Artists like him would coat their canvas with bitumen before painting in order to create an Old Master style. Bitumen pigment never actually dries out so that the surface of his paintings developed deep ugly webs of black cracks. Even today, and especially in a warm climate his paintings slowly and relentlessly continue to decay.

Stating the obvious, the best place for your painting is hanging on the wall. Two questions that inevitably pop up: should you put glass in your picture frames and, should the frames be screwed to the wall or hung from wire. It became the practice in the 19th. Century to ‘glaze’ paintings, that is, protect them with glass as the industry developed techniques to produce plate glass of relative large dimensions. Glass has the advantage of protecting your paintings against particulate air pollution, slowing the degradation of the painting and interestingly, making it more difficult to slice the canvas from its stretcher with a Stanley knife to steal it.

Naturally, if you have a painting on paper such as a watercolour, a valuable print or a painting in tempera or gouache it must always be under glass. Glass, however, has its drawbacks; paintings in dark browns and deep reds, colours you meet in works by Hogarth or the 17th.century Dutch school will act as mirrors reflecting back the viewer’s image and make the picture itself difficult to see clearly. In the past, glass was a very difficult material to manage, it was heavy, cracked easily and the resulting shards dangerous to both painting and person. Today one can use a sheet of transparent acrylic resin which makes an adequate substitute for real glass.

On the question of the theft of paintings, a recurrent preoccupation to picture owners on the Riviera, screwing the painting’s frame to the wall makes it more secure. One however has to consider that, in the case of fire, it slows down considerably ones ability to remove the picture quickly and in safety. Another drawback is that the change of seasons or air conditioning, briskly switched on and off, can hamper a framed painting’s natural ability to expand and contract. In recent weeks the author examined two beautiful Flemish Old Masters in Monaco where the artists had painted on panels that had split seriously along the grain of the wood.

The collector was a yacht owner where, apparently the rule is; nail down for safety everything that moves. By rigidly fixing these Old Masters into frames screwed tightly up against the walls with no room to contract and expand according to the seasons the result was very ugly cracks visible on the paintings’ surface.

On the Riviera strong sunlight is a continual threat damaging not just watercolours, drawings and prints but oil paintings also. Careful collectors hang watercolours for a limited time in a shaded area lacking direct sunlight. Very early on, the deleterious effects of light on the permanence of watercolours was recognised by far-seeing collectors. In 1900 Sir Henry Vaughan a wealthy art lover bequeathed 70 Turner watercolours to the National Galleries of Ireland and Scotland on condition that they be exhibited in the month of January only, when sunlight is weakest.

Oil paintings can be bleached by strong sunlight. The varnish covering the picture tends to become milky coloured and develop a cataract-like opacity that obscures the painting and needs eventually to be removed. The colours the painter used, especially the blues, greens and reds can fade, become black or brown and these transformations in serious cases are irreversible. On has only to recall the infinite number of Madonna and Child paintings in art museums where the mother of Christ is wearing a dark or black mantle that, when the artist painted it, was a bright blue

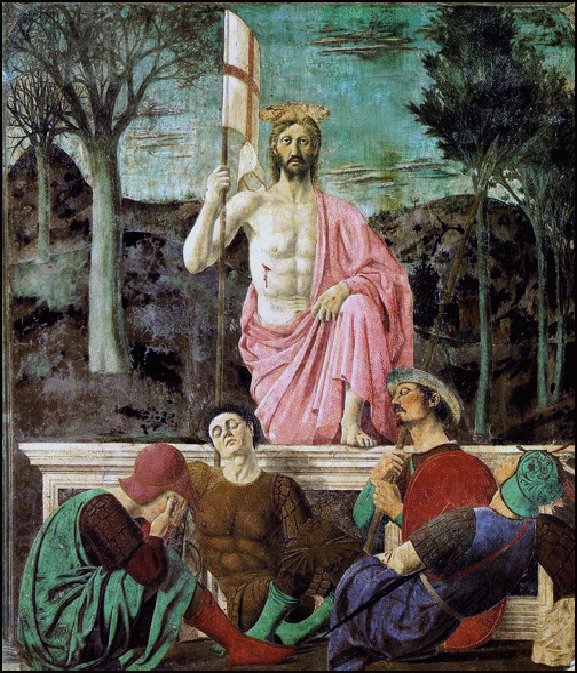

Piero della Francesca, Resurrection of Christ c.1460

Museo Civico of Sansepolcro, Tuscany, Italy. Over time,

the landscape’s green colours have darkened to brown.

When framing prints, watercolours, drawings or prints one tends to reach out for materials close to hand, practical and that do the job adequately such as masking tape, cellotape and scotch tape. Commercial adhesive tapes are very dangerous for the safety and the life of works of art done on paper. They deteriorate very fast in warm surroundings like the Côte d’Azur because they contain rubber-based or acrylic polymer adhesive. Adhesive tapes ooze a sticky residue that penetrates paper and, in the final stages of deterioration are very difficult to remove. You should use, instead, self adhesive archival-quality linen cloth tapes: they do not deteriorate and are easy to remove safely.

Hang your paintings in surroundings where you feel comfortable, with an equitable temperature and humidity and no excessive sunlight. Your paintings will feel equally at home and will survive to provide pleasure for many generations to come.