A (Short) History of Naughty Pictures

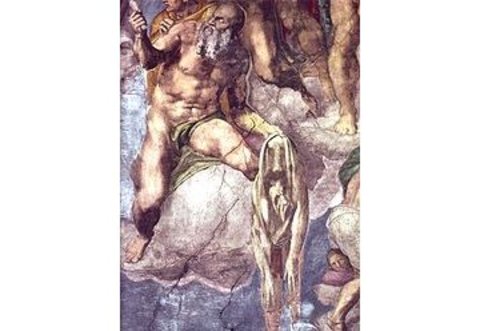

Fragments of naughty art survive as red-Attic vase paintings from classic-era Greece, Tarquinian Etruscan tombs and Pompeian frescos. To meet the demand of the profitable private collector, Italian Renaissance artists often painted scabrous subjects. The rediscovery of Greek and Roman classical art and Michelangelo’s aggressively naked male and female figures in the Sistine Chapel Last Judgment encouraged the trend.

St. Sebastian was a young Christian nobleman in an archery regiment, condemned to death for his faith at the hands of fellow officers by the emperor Diocletian. The saint was a favourite of those High Renaissance clients who enjoyed seeing paintings of a handsome young full-length male nude tied to a tree with his body pierced with arrows, and writhing in a suitably restrained manner.

That paintings of St. Sebastian should have been such a persistent feature of Italian Renaissance art and be so admired by fellow male tourists often baffled the innocent English traveller in nineteenth century Rome. Oscar Wilde was one such enthusiast. He belonged to a group of contemporary intellectuals who encouraged the cult of St. Sebastian; the probable reason he is considered the unofficial patron saint of homosexuals.

The Counter-Reformation soon put a stop to that. In the council of Trent’s 1564 decision to discourage the depiction of the nude in art, Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel masterpiece barely escaped the ensuing iconoclasm. A year later, by which time Michelangelo was dead, the Vatican commissioned Daniele da Volterra to paint trews on the naked figures in The Last Judgment. Six months later, when the Pope died unexpectedly da Volterra had to halt his repainting to make the Sistine chapel available for the new Pope’s election. The scaffolding was never replaced and the artist abandoned the project not, however, before gaining lasting notoriety for having put pants on the nudes in Michelangelo’s masterpiece. His nickname amongst fellow artists became Il Braghettone (the trousers-painter).

In Victorian England, Michelangelo’s nemesis, Il Braghettone was replaced by nightshirt painters. In the spirit of their sixteenth-century predecessor, they painted nightgowns over parts of many Renaissance Holy Family paintings where the Christ child is shown naked. It was a brief iconoclastic period when an important aspect of Christian iconography the concept, Christ born as a man and depicted as a naked baby, was lost.

Your correspondent, when the Irish National Gallery’s Old Masters conservator, encountered many examples of such Victorian prudery. Fortunately, by the nineteenth century, these pictures were usually covered by substantial coats of ancient varnish over which the Victorian artists painted their nightshirts. The varnish protected the work of art’s original colours from repainting damage and made it easier to remove. The Victorian repainting, inadvertently, protected the original colours from atmospheric pollution so that the painting, after restoration, would reveal its hidden beauty.

When the ageing Leonardo da Vinci moved to Amboise in 1516 the art world’s centre of gravity shifted to France where artists took a more light-hearted approach to art. Leonardo’s overwhelming presence and Italian Mannerist artists working at the palace of Fontainebleau in the 1500s introduced the Renaissance and a more relaxed pre-Reformation style into France. The Fontainebleau school privileged a particular type of feminine beauty of tall emaciated figures with small breasts, in Baroque Michelangelesque poses.

Later, robust large-bottomed Peter Paul Rubens females found favour with French painters. They would have seen Rubens at work during his 1625 visit to Paris to paint the cycle of Marie de' Medici and Henry IV, her husband, now in the Louvre.

Rubens influenced French artists including the Rococo painter François Boucher into the 1700s. Boucher embodied the artistic freedom and the French concept of beauty in the reign of his patrons Louis XV and Madame de Pompadour. He favoured voluptuous underage models in paintings that contain more than a hint of eroticism. The Blond Odalisque features the 14 years old nude Irish model Marie-Louise O'Murphy. The preliminary drawing for the painting, done in red & white chalk and lead pencil on paper, showing her nude lying tummy down on a chaise-longue was bought in 2007 by the Dublin National Gallery. About 1750 when Boucher completed the painting Louis XV acquired Miss O'Murphy, for a considerable sum of money. as his mistress.

The French Revolution created painters like Édouard Manet escaping the dead hand of Academic tradition, its monopoly over the art market, rules of what was suitable subject matter, a painting’s craftsmanship and finish and not least, academic notions of ideal beauty. While a fully paid up member of the French political establishment, Manet’s avant-garde style consciously clashed with that tradition. The precursor of the impressionists shocked the French, mocking the idyllic female models one expected to find in paintings by Titian or Poussin that the passage of time had sanctified. This is illustrated in his large canvas done in 1863, Le Déjeuner sur l'Herbe. It shows a naked woman sunbathing in a forest clearing in the company of two fully dressed men and another woman, clothed, in the background. She looks out in a brazen manner at the viewer.

The saucy seaside postcards published by the English artist Donald McGill with their mildly risqué humour achieved great success between 1904 and 1962. They appealed to newly emancipated Lancashire cotton-weaving mill and Manchester factory workers on their hard-won two weeks annual holidays by the sea at Blackpool. However the State censor was still active. In 1954, a British prime Minister Harold MacMillan used the 1857 Victorian Obscene Publications Act to prosecute and fine McGill £50. The sentence hastened the demise of English naughty picture postcard art.

Il Braghettone is not dead. He re-emerged recently still moving in Rome’s political circles. His target, a version of the 17th century Venetian painter Giambattista Tiepolo’s Truth unveiled by Time. The large canvas shows a lightly clad young woman displaying her well-developed right breast. This is Truth, lying in the arms of a white-bearded elderly man, Time. The painting forms the background to Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi’s Rome press conferences.

Apparently, thinking it necessary to avoid associating prime minister Berlusconi with a woman’s breast, in August 2008 his entourage, in order to conceal Truth’s nipple, painted over her breast with a coat of fresh paint. Berlusconi’s spokesman’s half-hearted justification for the gratuitous censorship was that, after all, the painting was not the original.

Even Antonio Paolucci, director of the Vatican Museums, an institution not short of pictures and statues of naked men and women admitted to being perplexed by this rather odd act of vandalism.

The Blond Odalisque