The Adventures of Rembrandt

The adventures and the misadventures of the world's most famous Old Master Rembrandt is the most modern of the Old Masters. In this series, his life and adventures in seventeenth-century Amsterdam are a reflection of the lives of all struggling artists, today as well as yesterday.

TWO THOUSAND YEARS AGO, Pliny the Elder, an ancient Roman writer, warned his readers that artists were best avoided; unpleasant people, thieves and grave robbers. Despite the romantic aura that artists acquired at the hands of nineteenth-century French writers, their existence in the two millennia since Pliny has frequently been short and brutal. Anthony Flinck, father of the artist Govert who worked as a journeyman with Rembrandt about 1633-35, was strongly convinced that his son's chosen trade would inevitably condemn him to a life of loose women and strong drink. It is perhaps understandable that some artists of Rembrandt's era, including Govert Flinck himself and Jan Steen, took the easy way out and married into money. Steen ran a licensed premises in Rembrandt's birthplace Leiden, an indication of the superior profits to be derived from a tavern.

The Adventures of Rembrandt are available for book illustrations, annual reports, paper and packaging, giftware, Rembrandt-related products. You can license them in the following format:Original transparencies in 6 x 6 cm. (2¼ in.) format, high-resolution RGB drum scans on Cd or efficient and quick FTP upload.

Rembrandt's signature

There is an immense void between the pecuniary value of a Rembrandt and the paintings of his colleague and studio collaborators, first-rate artists the likes of Jan Lievens, Willem Drost, Govaert Flinck, and the legendary Carel Fabritius. The latter?s paintings were often attributed to Rembrandt van Rijn. The rights Rembrandt acquired when he took on apprentices makes the identification of genuine works by the master very complicated. The apprentice?s Articles of Indenture allowed him to sign his students? paintings as being by his own hand. This created much subsequent confusion, the Rembrandt signature on a painting might be genuine but not the artist. The dress of Rembrandt's clients or protagonists as in the figure to the right, is usually contemporary 20th century and later.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

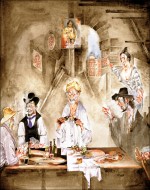

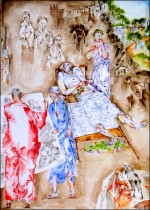

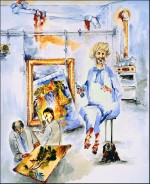

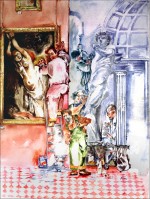

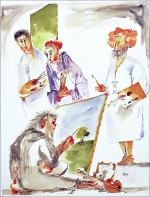

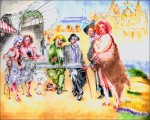

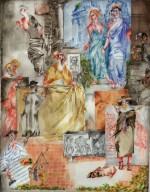

Rubens visits Rembrandt

Rubens visits Rembrandt - Rembrandt, surrounded by his cronies, Van Gogh and Toulouse Lautrec is using a panel painting portrait of Helen Fourment (Het pelsken) to the artist, Peter Paul Rubens?, dismay. The background is a view of the Halfpenny Bridge (The metal bridge) through the arches of old Dublin onto the 18th century Georgian buildings on the other side of the river Liffey. A Sybil in 18th century neo-classical costume points to the only other female oil paintings visible in the studio, Rembrandt?s `A Woman Bathing`, (London National Gallery). Matthew has, in this watercolour, attempted to evoke the composition and colour of the Dutch Old Master Benjamin Gerritsz Cuyp. Dordrecht 1612 ? 1652.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

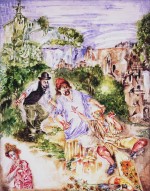

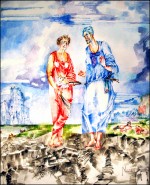

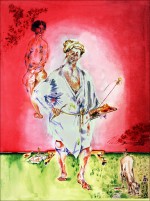

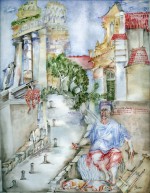

`Sure, Rembrandt is a great lover of nature`

The two maidens bathing on the rocks and being observed by Rembrandt are backed by a landscape composed, partly, of an ancient bridge in Ceriana, in the Italian Riviera hinterland. The church and the Georgian market building that Rembrandt is depicting on his canvas are details from Matthew's watercolour of Barnard Castle, Co. Durham UK. The Greek Sybil who points towards Rembrandt wears a sash that the artist has highlighted using pure gold pigment.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

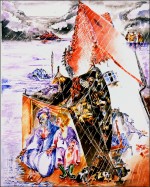

`Rembrandt belongs to the 'take-no-prisoners' school of painting.`

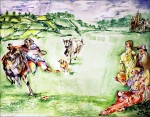

Rembrandt belongs to the 'take-no-prisoners' school of painting as the ancient Greek Sybil in the lower left of the painting points to the crime being committed; the death of Vincent van Gogh at the hands of a jealous Rembrandt. Their mutual companion, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, looks on horrified as the Old Master wields his knife in the manner of Abraham in the same artist's 1635 "The Sacrifice of Isaac" now in the Hermitage Museum. The scene takes place against a background of the landscape of the Principality of Monaco that the artist painted on site a few years previously and subsequently incorporated into this painting.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

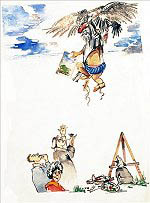

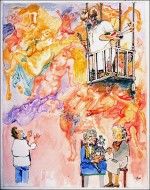

The apotheosis of Rembrandt van Rijn

`It's the one way he would have wanted to go.` This watercolour is the earliest of Matthew's, `The Adventures of Rembrandt` cycle. The composition was inspired by Rembrandt's 1635 drawing and the finished oil painting, `The Rape of Ganymede` both in the Staatliche Kustsammlungen, Gem?ldegalerie, Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

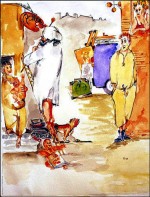

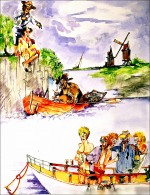

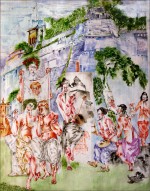

`There goes the neighbourhood`

There goes the neighbourhood, an older expression that is somewhat similar to the more recent NIMBY (not in my backyard) to define residents of a quartier that see their way of life, or the value of their property being compromised by an influx of foreigners, the poor, people of a different culture or engaged in undesirable activities or, artists. The fear is often justified when social upheavals result in farmers, for example, being priced out of their property by surreptitiously introduced planning regulations favouring property speculators as happened in Victoria in Australia when the artist lived there or, land grabbing from the indigenous peoples of the Amazon. In poorer urban areas the newcomers' encroachment put pressure on overstretched public resources. An invasion of artists will, in modest neighbourhoods on the other hand, cause equal damage, introducing the blight of gentrification and pricing the locals out of affordable accommodation and services.

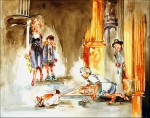

In 1660, the latter part of his life, when he fell on hard times, Rembrandt was obliged to move to a very poor part of Amsterdam, the Jordaan. Matthew Moss shows Rembrandt hanging up his shingle upon his arrival and surrounded by his wife, his children and the dog. He is looked on askance by his new, working-class neighbours while in the rear is his kombi van, loaded with the materials of his trade, canvases, portfolio loaded with drawings, his easel.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

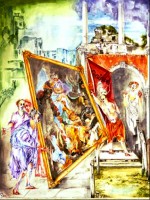

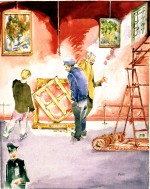

Well, it looks like, once more back to the restoration lab for Rembrandt

In the background we see the massive ancient stone walls that defend the Principality of Monaco on the French Riviera. In the middle distance, the red banner hanging in front of the cut-stone gateway announces an exhibition of Rembrandt's paintings. In the foreground four navvies are hauling his 'Blinding of Samson' *over a moat.

The curator, garbed in the classical manner, looks on horrified while the hauliers attempt to circumnavigate the mooring bollards along the boardwalk. They realise that they are loosing control of the large canvas weighed down, in addition, by its massive gilt frame. They are unable to raise it sufficiently and one of the sharp pointed wooden posts rips through and penetrates the taut canvas to reappear through the painted surface of Rembrandt's masterpiece. So, it looks like it's, once more, back to the restoration lab for Rembrandt.

The Marriage Feast at Cana by Veronese inspired, Matthew Moss, with his background as a paintings conservator with the National Gallery of Ireland to create this 'Adventures of Rembrandt' painting. The massive 6.66×9.90 meter Venetian Mannerist canvas, Napoléon's war booty from his Italian campaign of 1797 was severely damaged, in July, 1992. While being rehung at the Louvre museum after a $1 million restoration and conservation makeover museum technicians trying to hang Veronese's masterpiece lost control of the enormous painting. The curators could not prevent it falling onto the points of the scaffolding framework's metal bars, five of which punched holes through the canvas. The painting had, shortly before, been relined and restored. Hence Matthew's caption to his own interpretation to the event of, once more back to the restoration lab.

*Frankfurt Städelsches Kunstinstitut

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

Rembrandt Gets Arrested Near a Bank Vault

Rembrandt laments, "My paintings have become so rare and priceless, that they won't let even me go near them."

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

Rembrandt's stolen Masterpiece

Venus comforts the famous Dutch Old Master; `Don't let it get you down, Rembrandt, if your masterpiece has gone walkabout. It will turn up, eventually, hanging in a respectable international museum` Rembrandt is in a demoralized state following the disappearance of his masterpieces. He is consoled by the Morgantina Venus, while the bronze Athlete of Lysippos - both of which are, presently, in the Malibu, Paul Getty museum - makes an ironic comment on the scene.The earliest documented example of art looting is the relief sculpting on the inside walls of the arch of Titus in Rome. The scene depicts Roman soldiers returning with treasures looted from the Temple of Jerusalem in 70 AD.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

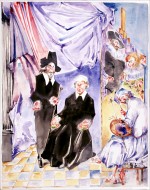

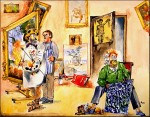

'Us Old Masters often spend years painting the perfect portrait.'

Two Clients of Rembrandt have waited so long for him to finish their portrait that they have aged visibly in the meantime. Rembrandt was notoriously difficult to deal with and patrons who commissioned portraits had to be prepared to wait many years and endure innumerable sittings before he would complete the painting. (It is a fault to which, later, Cezanne was subject). When the Sicilian nobleman, Don Antonio Ruffo finally, after long delays, received, Aristotle with the bust of Homer he had commissioned from Rembrandt he discovered that the artist had painted it onto a support put together from a patchwork of odd-sized linen strips. The artist had sewn together scraps of canvas to make up a bigger canvas. It is no surprise, therefore, that when the client finally received the portrait of himself his wife or member of his family it would be rejected because the likeness was unsatisfactory, or the style of clothes the sitter is wearing had gone out of fashion. This, (in the case, say, of the portrait of a young girl) was to be expected when the execution had taken, maybe, six or more years to complete. In the Rijksmuseum's, Bartholomeus van der Helst 1642, Portrait of Andries Bicker the subject is wearing a millstone white collar. A later portrait of his son, Gerard Bicker is wearing a flat collar. It seems that, in this example, Rembrandt has spent rather too long on painting the perfect portrait.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

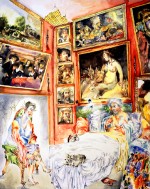

The Rembrandt Collection

“Couldn’t you just try to let go of a few paintings?†Often, the greatest admirer of an artist’s work was the artist himself. Legends exist of clients threatening and pleading with Titian and, later, Rembrandt, to hand over the painting they had commissioned and often paid for in advance. Rembrandt’s clients are reputed to have waited until the artist was away from the studio in order to enter and reclaim their painting. In the case of Titian it was the artists desire to improve continually by modifying and reworking the canvas that made it so difficult for his clients. This obsession for perfectionism forms part of the contemporary Bonnard myth. He was reputed to visit museums armed with colour in order to retouch those painting of his with which he was dissatisfied.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

The Dormition of Rembrandt van Rijn

Rembrandt van Rijn is laid out in his studio before burial. The dark, cavern-like background is in the style of his late paintings. Mourners and a distraught Sybil look on while eager art dealers remove any paintings by the Master that remain. (A similar incident occurred upon the death in Paris of Modigliani in 1920). A worried terrier grips what was probably Rembrandt's final canvas “The Return of the Prodigal Son†while looking anxiously towards his late master. The landscape of Monaco is in the distance. The title of the painting refers to the Virgin being taken to heaven upon her death. It was a favourite subject in medieval Greek orthodox painting treated by, amongst others, the early El Greco. Italian artists did not adopt the subject until the Counter-Reformation and the Council of Trent, 1545 - 63. Federico Barocci was the principal exponent of the bright emotional colours and theatrical mannerism of the new style. The most notorious version of the “Death of the Virgin†is Caravaggio's. Rejected in 1606 by the church of Santa Maria della Scala in Rome for which it was intended, this massive canvas is now in the Louvre.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

Judith with the Head of Vincent van Gogh

"You were only meant to cut off van Gogh's earlobe". On a rocky headland overlooking the Principality of Monaco, Rembrandt is remonstrating with Judith who holds a platter containing the decapitated head of Vincent van Gogh. In the middle distance van Gogh is lying sprawled out amidst the scattered remains of his palette and unfinished landscape painting. Behind the artist is the eighteenth century Fort Antoine and beyond, the Cap Esterel mountain range. To the left you see Monaco's Musée Oceanographique. The painting by Matthew Moss owes its inspiration to Judith with the head of Holofernes an Old Testament subject very popular with Baroque artists. A painting of about 1620 in the Uffizi, Florence by Artemisia Gentileschi shows in gory detail Judith decapitating the invading Assyrian general, Holofernes. Rembrandt is not known to have depicted the subject although some scholars suggest that his Flora* began life as a Judith with the head of Holofernes. He was influenced by a Peter Paul Rubens painting of the same subject done in 1616. Another interesting version of Judith with the head of Holofernes, attributed to Carl Fabritius, Rembrandt's pupil, is in the Old Masters section of ArtMonteCarlo.com http://artmontecarlo.com/image_details.php?painting_id=589 *London, National Gallery

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

The Deluge

“We always knew that, someday, your canvas would be appreciated.†The Night Watch of 1642 began the slow decline in Rembrandt’s fortunes. It was the period when Geertje Dircx who, hired to look after his infant, Titus, put pressure on him to marry her and, eventually, took him to court in 1649 for breach of promise. In settlement, Rembrandt paid Geertje a life pension; this, coinciding with a slowdown of painting commissions, aggravated his already deteriorating financial circumstances. In 1653 under threats of repossession the artist was forced to take out short-term high-interest-bearing loans to pay off the owner of his home. Unable to meet the notes as his various creditors called them in, bailiffs seized his property, including the house, his collection of Old Masters and his own paintings and drawings. In subsequent bankruptcy proceedings the prices realized by the various sales were insufficient to pay off the money he owed. In The Deluge the van Rijn family is experiencing one of the frequent devastating floods that, throughout history, the Dutch population has had to face. In this case the artist is, at least, protected by the waterproof qualities of one of his larger oils, 'The Night Watch' or, 'The Company of Frans Banning Cocq and Willem van Ruytenburch'.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

A Likeness of Fido

â€They want to know, would you do a likeness of Fido? â€

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

Rembrandt and Potiphar's Wife

“That’s me out of here then, no more Rembrandt, society painter.’†The story of Joseph and Potiphar’s wife the biblical figure whom the wife of a top Pharaoh official tried unsuccessfully to seduce, is a favourite motif in Renaissance painting. Rembrandt treated the theme in an etching of 1634. The National Gallery of Art, Washington has a Rembrandt oil on canvas of 1655 treating the same subject. In Matthew's version of Joseph and Potiphar’s wife the landscape in the background is Cap Esterel seen from the hills of Monaco. Behind Rembrandt’s seducer, above the unmade bed is the painting, Satyrs and Nymphs. You can view the original of this rare painting by the ill-fated Dutch artist Johannes Torrentius (1589 - 1644) who was arrested and died in a Dutch prison, at, http://artmontecarlo.com/upload/98-Fauns%20and%20Nymphs%20by%20Johannes%20Torrentius-La rge-0602-126.jpg.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

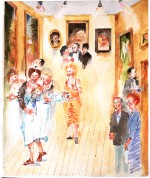

Rembrandt400

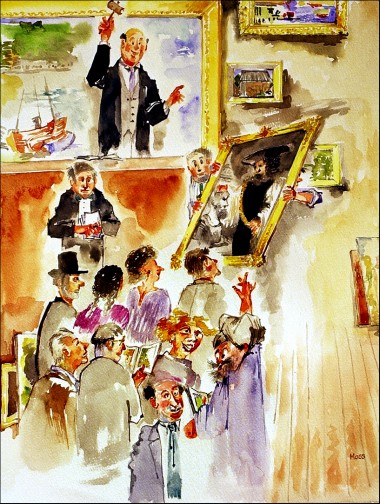

Title: “This Rembrandt better be good!â€

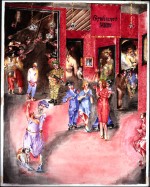

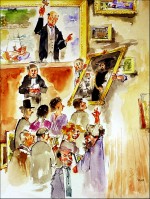

The composition of Rembrandt400 (painted to celebrate the 400th Anniversary of Rembrandt’s birth) is based on Il Ridotto di Palazzo Dondolo a San Moisè*(The foyer) by Francesco Guardi in Venice’s Museo Ca’ Rezzonico. The artist has changed Guardi’s horizontal composition to vertical. Matthew Moss has, also, converted the Venetian artist’s rich claustrophobic closed-in foyer of this Venetian casino to the equally hot-house atmosphere of a contemporary high-profile Old Masters exhibition.

The gamblers and miscreants in the Guardi painting have been replaced by the overwhelming presence of security guards, controls and surveillance that dominate Rembrandt400. Concerns for the security of high-value art is now omnipresent in famous-name big profit-generating exhibitions. Similarly, Guardi’s beautiful people, and hangers-on shown on the Great Staircase of the gaming house, are illuminated with chandeliers running horizontally across the top quarter of the canvas. In Rembrandt400 they are replaced, instead, with security cameras. Matthew created the highlights of the cables securing the camera using fine pure liquid gold (known as shell gold) that he burnished so that it reflects slightly from the surface, a technique known to medieval illuminated manuscript painters, including the artist's distant ancestors, the creators of the Book of Kells in Dublin.

*The casino of Palazzo Dondolo was, in his last years, the home away from home to John Law a brilliant Scottish economist . His ante litteram theories on money brought about the economic collapse of Europe and in particular, France in 1720. He is buried in the central nave of the nearby church of San Moisè.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

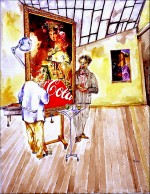

“These are all genuine Rembrandts; after I’ve added my signature.â€

There is an immense void between the pecuniary value of a Rembrandt and the paintings of his colleagues and studio collaborators, first-rate artists the likes of Jan Lievens, Willem Drost, Govaert Flinck, and the legendary Carel Fabritius, even if, because of their high artistic quality the latter’s paintings are often mistaken for works by Rembrandt van Rijn. The rights Rembrandt acquired when he took on apprentices complicates the identification of genuine works by the master. The apprentice’s Articles of Indenture gave Rembrandt the right to sign his students’ paintings with his own signature. The artist was likely to avail of this privilege when his pupil's painting was of a high quality. This created much subsequent confusion; the Rembrandt signature on a painting might be genuine but the painting was, in fact, done by another artist.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

†They say some quite important artists come hereâ€

Rembrandt, seen with Saskia van Uylenburgh on his lap, is a frequenter of the Bar des Artistes. Here, Matthew Moss' inspiration is Rembrandt and Saskia (or, The Prodigal Son) in Dresden’s Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen. Amongst noteworthy frequenters of the bar are the elderly Leonardo da Vinci in the foreground, Rembrandt's inseparable friend Toulouse Lautrec with Vincent van Gogh and a barely noticeable Pablo Picasso in the background.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

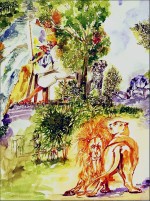

â€Let Rembrandt finish his masterpiece; then we eat him.â€

The two hungry, but patient, lions belong to a similar composition found in a number of Jan Brueghel de Velour paintings.Their origin may be a prototype by Peter Paul Rubens either a drawings or lost painting.The background and waterfall against which the oblivious Rembrandt works is based on a detail in a watercolour by Matthew Moss of the Val d’Aoste alpine landscape.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

“You’re certain, are you, that Rembrandt himself sold you this original?â€

Matthew Moss' watercolour was prompted by a 1950s fable by the post-Joycean Irish writer Myles Na Ghopaleen in the Cruiskeen Lawn column of the Irish Times. . . .“Are Our Plaster Casts Genuine? Seventy-five per cent. of the pictures in the National Gallery are fakes. The next time you are there take a penknife to the fine El Greco and scrape away about a quarter inch of the picture where your handiwork will be least noticed. You will come across a banner for the 1903 Irish Language Procession in Wexford, in which my uncle had the distinction of riding the first bicycle ever made in Ireland. Keep scraping and under that again you will find a bizarre ad. for a patent cattle drench fashionable in the ‘eighties. (When you are satisfied, and have thoughtfully put away your knife, be sure to gather up your little mess of pinxorial dandruff, and leave the place as clean as you found it) . . .".

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

“You couldn’t come back another day? Rembrandt’s on a very tight schedule.”

The Night Watch of 1642 began the slow decline in Rembrandt’s fortunes. It was the period when Geertje Dircx who, hired to look after his infant, Titus, put pressure on him to marry her and, eventually, took him to court in 1649 for breach of promise. In settlement, Rembrandt paid Geertje a life pension; this, coinciding with a slowdown of painting commissions, aggravated his already deteriorating financial circumstances. In 1653 under threats of repossession the artist was forced to take out short-term high-interest-bearing loans to pay off the owner of his home. Unable to meet the notes as his various creditors called them in, bailiffs seized his property, including the house, his collection of Old Masters and his own paintings and drawings. In subsequent bankruptcy proceedings the prices realized by the various sales were insufficient to pay off the money he owed.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

“You make money from art only when the insurance kicks in.â€

In Dublin, the capital of Ireland, a prominent art gallery was, for a period in the later part of the 20th. century plagued by a series of burglaries, most particularly when exhibitions were being held. These innocent but hopeful law-breakers had come to the conclusion that the relatively high prices quoted in the exhibition catalogue made the paintings exhibited desirable prey. They would be easy to steal and to sell on, if not, they imagined, quite for the full catalogue price. It took some years for the thieves to discover the realities of the art market. The break-ins and the theft of paintings from artists’ shows gradually ceased, when this dawned on them. All through the period, the only persons to gain to some extent were the bemused artists who were exhibiting and who were as a result of the theft of their paintings indemnified by the insurance companies. The unexpected cash benefit they received was often over and above the meagre returns resulting from the show itself.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

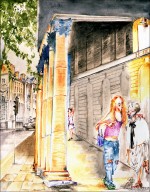

“Mom, does dad really need to be an artist?â€

An elderly and bearded Rembrandt, pavement artist, practices his trade beneath the classical colonnades of Gandon’s ancient Irish House of Parliament, now the bank of Ireland in Dublin. Incessant soft Irish showers discourage painting outdoors . However, Rembrandt has chosen his work-site astutely; it is protected and, being in the centre of the city, much trafficked by pedestrians. This genial location guarantees him a steady income, if an exiguous existence. In in mid-20th century Dublin children, suspected of displaying undesirable artistic tendencies were shown example of pavement artists working in this spot as the unpleasant future likely to await them should they choose to become artists.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

â€Sure I bid on my own paintings; by doing that it makes them worth more.â€

During his years of prosperity Rembrandt attempted to corner the Amsterdam fine-art market. The artist was an enthusiastic and regular frequenter of Amsterdam’s public auctions, and often prepared to pay high prices for the engravings of well-known artists particularly of Lucas van Leyden (1494-1533), a fellow painter of the previous generation who, like Rembrandt, was born and worked in Leiden. His strategy, in order to establish a strong market for his own etchings and so keep prices high, was carefully to retain possession of his original engraved copper plates (preventing others from printing from them) and simultaneously buy up such of his etchings as came on the market. Rembrandt’s attempt to control the market in Rembrandts, however, necessitated much larger financial resources than he could muster. It was one of the causes of his subsequent financial difficulties.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

"The Art Market showing signs of the global slump? Methinks not !"

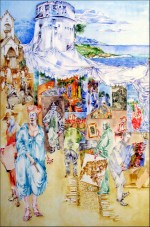

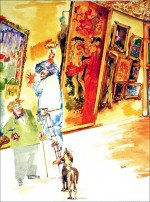

Damien Hirst a British artist realized one hundred forty million US dollars in a Sotheby's September 2008 art sale during a world-wide financial market crash. As the fine-art market sails blissfully along despite the financial chaos and disasters Rembrandt visits the booming fine-arts section of the San Romolo Fair. The centuries-old open-air market takes place every year on October 13th in San Remo on the Italian Riviera. Rembrandt is surrounded by dozens of stands that display for sale canvases, framed paintings and prints. Spectators and art dealers crowd Sanremo's narrow stone-clad streets examining the works of art on display, or carrying away their purchases in the direction of the medieval cathedral of San Siro on the top left of Matthew Moss' painting. Rembrandt van Rijn is accompanied by his two perpetual companions, Vincent van Gogh, and, in the background hurrying to catch up, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. The basilica of San Siro, is a medieval cathedral of the twelfth century built over the remains of an earlier, Paleochristian church. The style of the church has altered over the centuries because of changes to church liturgy and not least, damage caused when Sanremo was bombed by the republic of Genoa's navy in June 1753 and again by the American navy in 1944.

The painting you see hanging on the extreme right in the art market stalls is a recent oil on canvas by Matthew inspired by Giorgione's 'La Tempesta.' Entitled S.Devote*, it is a view of the Principality of Monaco. In it's foreground is the boat in which the legendary Saint Dévote, who is the patron of the Principality, was washed up on the coast of Monaco. She is seated to the left of the fortified medieval city's walls, holding a palm branch the symbol of a martyr. To the right of the cathedral of Saint Siro you will find a fortified tower, the 'Torre Ciapela or Chiapella.' This was built in the mid-sixteenth century to protect Sanremo's inhabitants from the Saracen pirates of the Sinai peninsula who, up to the eighteenth century, frequently raided the Riviera coast. In style, it is a little similar to the Martello towers built around Ireland in the early nineteenth century. The impressive building has one-meter-thick stone walls, once part of the Sanremo city fortifications.The top is furnished with openings to provide a line of fire for the defenders.

The tower was restored in 1960, but not before real-estate speculators tried but failed one night at the end of December 1959 to demolish it. When the artist was living in the old gold mining town of Ballarat in Australia during the 1970s a similar attempt was made on an historic monument. This time the buildings speculators, working on behalf of a multinational American fast food company, sent in demolishers before dawn to pull down an important nineteen-century building of bluestone with original cast-iron-clad verandas before being intercepted by the authorities. Matthew painted the background landscape from his studio in the Principality of Monaco, a view of the rocky coastline and blue Mediterranean looking towards Roquebrune-Cap Martin. *http://artmontecarlo.com/image_details.php?painting_id=669

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'There's a countryman of yours here; says he needs to talk to you.'

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

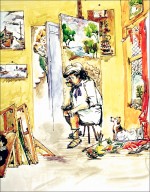

'Young Rembrandt ought to think twice before dedicating himself to art, otherwise he will end up like van Gogh.'

The young Rembrandt suffers unnecessary and unwanted advice from curious onlookers, the fate of all artists who work outdoors.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'Thats all We Need is More Artists'

Rembrandt, banging on the window of the locked gallery, is attempting to gain entrance to show examples of his new paintings while the director and staff hide from him around a corner.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'Get rid of him, we are up to our eyeballs in Rembrandts.'

The scene takes place in the luxurious interior of Monte-Carlo’s legendary Casino. The building, built in 1863, with its fin-de-siècle gold and bronze architecture and gilt stucco reliefs is the work of the architect Charles Garnier, designer of the Paris Opera and numerous churches, private villas and public buildings along the French and Italian Riviera. The rich golden Rembrandt-like tints of the background act as a foil to the green baize of the table and overhead lamps that frame the desperate Rembrandt and his assortment of pictures.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'So I says to him I say, Rembrandt, don't take an apartment under Michelangelo .'

Based on a scene from the English comedian, Tony Hancock's 1960 classic film of an outsider The Rebel. Before moving from his London bedsitter Hancock’s chef d’oeuvre the massive marble Aphrodite at the Waterhole, goes through the ceiling of the flat below. In the background is Rembrandt’s Danae now in the Hermitage. In June 1985 it was attacked and severely damaged with sulphuric acid and slashed by a fanatic It required over a dozen years of meticulous conservation to save one of the museum’s most significant masterpieces.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'Leaving Rembrandt alone with his models never worries me.'

Mindful of Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey, the road movie of its day, his wife has Rembrandt securely tied up, like Ulysses, to prevent him succumbing to the Siren call of his young and attractive model.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'Oh, that is Rembrandt, he will do anything to get talked about. '

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'Of course It was a genuine Rembrandt, didn't the Mafia take it.'

A guard explains to the young onlooker that the mafia steals only genuine Old Masters.

The general composition, the light streaming in from the right and illuminating the subject, is inspired by Caravaggio’s, The Calling of Saint Matthew in the Rome church San Luigi dei Francesi. Numerous thefts, attributed to the Mafia, of Old Master painting took place in Italy in the latter part of the 20th century. One of the most clamorous was the theft, in 1969, apparently to use it as a form of barter between different Sicilian criminal clans, of another Caravaggio, The Nativity with Saints Laurence and Francis belonging to the church of San Lorenzo in Palermo and never recovered.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'Rembrandt is paying rather a heavy price for being famous.'

During a vernissage of his paintings the ladies of the free gallery cocktail circuit, the soup kitchens of the middle classes, embrace and worship an embarrassed and irritated Rembrandt.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'Even though none of them can paint for buttons, my dear, they do pay rather well.'

The attractive young model is surrounded by students of art, voyeurs of different sexes who obviously are talentless while Rembrandt encourages her to hang on in there, and think of the money.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'Let's get this straight; you want we go upstairs. Then, how many hours do I have to sit without moving?'

Rembrandt beneath the columns of the ancient Irish house of parliament, now a hotel, and propositioning, for strictly artistic purposes, a somewhat baffled young woman. In the background, the Georgian façade of the University of Dublin. The painting’s title, Underneath the Arches, refers to the song by Flanagan and Allen, English music-hall artists of the 1930s and 40s.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'He doesn't know much about art but he knows what he likes.'

Rembrandt is painting a girl balancing on a prancing white horse. The gorilla looking over his shoulder happily chomps on the artist's paint tubes. The broken chain around his ankle shows he has escaped from his cage at Monte-Carlo zoo, visible in the background.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'If Michelangelo can afford a wash and brush up, we're going to do the same for Rembrandt.'

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'Why is it you artists are so anti-social?'

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'Sure Rembrandt is depressed, they stole everything he had but left his paintings.'

Rembrandt in the midst of the desolation left by burglars who stole everything except his paintings. The manner in which most people value artists and view their creations is symbolized by the thief who, in the 1990s, broke into the British artist David Hockney’s residence. With a grasp of art economics most painters only dream of, he chose to steal electronic household objects only, disregarding completely the original Hockneys on the walls.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'After I completed the Night Watch things have not gone so well.'

Because of the poor economic climate, Rembrandt is, temporarily, working as a house painter.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'There are surprisingly few cattle paintings attributed to Rembrandt.'

Rembrandt rushed by a jealous bull; one of the many problems artists experience painting outdoors. The difficulty of painting outdoors is described in various paintings in The Adventures of Rembrandt; The Pavement Artist, Rembrandt en Plein-Air, The reasons Rembrandt is not known to have attempted cattle paintings may lie in the subject’s relative lack of importance in Renaissance art. Figure painting was considered a nobler art form requiring greater skills than that of the andscape or genre painter. The painting’s landscape is of the north county Dublin countryside. The bull dragging Rembrandt along with him refers to to Carlo Maratta’s painting, The Rape of Europa that the artist restored at the National Gallery of Ireland

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'What's with painting fake Rembrandts? I am Rembrandt!'

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'He is talented, undoubtedly; however, he doesn't have signing privileges.'

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

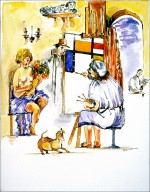

'It seems, my dear, your days as Rembrandt's model are numbered.'

Rembrandt’s model is preoccupied that he is abandoning the classical style for that of a modern Dutch painter Mondrian. The image of a young woman holding a cornucopia, a horn filled with flowers, fruits, and vegetables and a symbol of fertility and abundance developed in ancient Greek art. It is used frequently in Dutch and Flemish painting of the 17th century. The painting’s composition is based on the drawing by Samuel van Hoogstraten*, Young artist painting the portrait of a couple, circa 1640. 93rd. exposition du Cabinet des dessins, Musée du Louvre 1988 – 89.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'Come back another time when you have something more avant-garde to show us.'

Rembrandt exits an art gallery having learned that the market for his style of painting is past.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

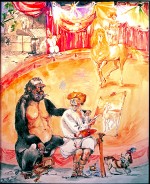

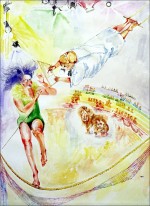

'Does it never occur to you, Rembrandt, how obsessive is your search for realism?'

Rembrandt goes to extraordinary lengths to capture the graceful beauty of the trapeze artist’s movement. The Dutch Old Master, in the manner of Degas, is attempting to capture the gracious movements of the girl on the trapeze. He considers himself, above all, a realist. This was the label that Thomas Couture attached to certain of his contemporaries, Corot included. He recognized that this obsession with realism was leading to the loss of the classical tradition and the lesson of the High Renaissance. Couture expressed his opinion on the dangers of naturalism in The Realist Artist now in the National Gallery of Ireland.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'Down below, that's Rembrandt painting; over there is his art agent with his yacht.'

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

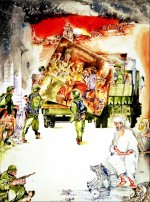

'Sure, we've been liberated, however, now they're liberating our works of art.'

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'The adventures of Rembrandt'

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'Rubens thinks that he is the bees knees with that new trophy wife.'

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

.jpg)

'It might have been less complicated had we bankrolled the show with a loan.'

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'It looks like the free market caught us unawares.'

Chinese hand-made oil paintings have destroyed the livelihood of local artists. Traditional artists no longer are able to compete. Rembrandt finds himself sitting under the fortified wall of the medieval Principality of Monaco. The Rock on which the ancient buildings and Prince’s palace sit, appear above him. A background to the artists , seen painting below, is the red brick and granite stone steps of the Porte Neuve leading up into the fortress.

A dejected and suffering Rembrandt sits on the left comforted by his female companion. Behind them stands a Saint Veronica-like figure holding a towel, on which is represented the head of the ageing Rembrandt. In ancient artistic iconography Saint Veronica is a pious woman who bathed Christ’s face on the road to Golgotha to be crucified.

Four Chinese artists, wearing their hair dressed in the Manchurian-style, who appear to have relocated to Monaco, are painting views of its forbidding rock defenses. On the bottom right centre, where two of the Chinese artists are seated on a rock, is a tiny Pekinese, painted in a warm sepia-black tint. The terrier is lying, on his back legs in the air while regarding the viewer. Another artist is standing above him with paint brushes in his left hand. In his right he holds an open scroll with the artist’s signature in Chinese characters.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'Bad luck Rembrandt, Leonardo got here before you.'

An ageing and disconsolate Rembrandt seated on the Escalier Daru entrance to the Louvre is accompanied by Gauguin, Toulouse Lautrec and Vincent van Gogh. In front of his Mona Lisa Leonardo, making Tour de France-winner gestures, is flanked by two maidens. The Italian Old Master and his masterpiece, surrounded by security guards, are being assailed by admirers and art lovers.

The Victory of Samothrace a classical statue of 220-190 BC, discovered on the homonymous Greek island sits at the head of the 1850s Escalier Daru. It forms part of the background framing Rembrandt van Rijn. Museum guards regard with suspicion the excluded and no longer fashionable Dutch master, unable, apparently, to gain entrance to the temple of beauty.

Rembrandt, is holding in his left hand his 1636 panel painting Susanna Bathing. In Matthew’s painting, the version Rembrandt holds is on canvas. To the right and partly blocking Susanna Bathing, is the artist’s faithful hound gazing mournfully into Rembrandt’s eyes. He has the typical characteristics of a stray, lean wiry and tan-coloured. The two female figures enclosing Rembrandt and his group are keening an Irish lament for the dead over the great Dutch master’s ill fortune.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

'In my opinion, Rembrandt is going through his Blue period, so he is.'

Rembrandt down and out, with his paintings hanging from the railings of a Georgian square in Dublin.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

Rembrandt Gets A Break

The premature announcement of his death forces Rembrandt to work overtime in order to meet the increased demand for his paintings. Against a background of the ancient Roman monument, the Trophee des Alpes on the French Riviera Rembrandt’s wife and a friend watch the artist stretching a large canvas helped by Toulouse Lautrec. To her left is visible the edge of the Night Watch as it appeared while still in the artist’s studio before the Amsterdam local authorities sliced off this piece of the artist’s masterpiece in 1715.

Other artists lending Rembrandt a hand allowing him to profit from this unexpected piece of good fortune are a stressed out Vincent van Gogh, the elegantly dressed Peter Paul Rubens and in the foreground, Pablo Picasso. The Seville oranges at his feet also encircle Rembrandt’s faithful hound sleeping below a late Roman sarcophagus from the Palazzo Corsini alla Lungara in Rome. Matthew is at the top left, signing the painting.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

Susannah and the Elders

The bathing Susannah, harassed by two Elders

While Rembrandt, who is painting her portrait, has his back turned, two lascivious characters amongst whom Gauguin and the artist importune and threaten Susannah, the virtuous wife of Joakim, saved in the nick of time by the prophet Daniel.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

Entry of Rembrandt into Monaco

‘It sure is a relief, so it is, that my creditors don’t know I’ve escaped here and they can’t dun me for my debts ‘

Rembrandt is known to have disappeared from Holland after the 25th. October 1661 because of the shame and the stigma surrounding his recent bankruptcy. He turns up in the ancient Roman town of La Turbie, on the outskirts of Monte-Carlo in French Provence. He reappeared in Amsterdam on 28th.August 1662.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy

This isn't the central bank

“Sorry boys, you’re in Rembrandt’s studio, the central bank’s next door”

Parisian Apaches break their way into Rembrandt’s studio, thinking it is the next door central bank.

Large image, details and buy

Large image, details and buy